Before I make any comments, I must correct the anachronism of some prior comments:

- Even if you skipped over the beginning of the first chapter, it should be clear from the pocket watch and all things western in the manga that it does not take place in the twelfth or sixteenth centuries but the nineteenth. Based on various details found in the manga, I'm guessing Otoyomegatari takes place mid-century (circa 1860, earlier would make the characters of Mr. Smith and the female Brit impossible).

- The story does not take place in Mongolia (East Asia) but in Central Asia in the general region of the Aral and Caspian Seas: from the maps in chapter seventeen and the prior progress of the story, the story begins just East of the Aral Sea but not far enough East for Qing Dynasty China to be a significant factor. (Later on, the location of the village the story starts in is specified to be near the city of Bukhara, Uzbekistan, and that's as far East as the setting ever gets. In other words, most of the groups in the story are Turkic, not Mongolic, and the political powers in play are Britain and Russia.)

- As with any other work, please read it for what it is, not what it isn't. This story is very definitely a historical slice of life. Note the lack of the action genre, and although it's labeled "drama," it's more like there are touches of drama here and there. Overall, Otoyomegatari is a more serious type of story (or heavier reading, one might say), thus the Seinen demographic (maybe I was a precocious little girl, but I doubt that's it).

The plot is essentially an interconnected episodic, moving from bride to bride, following Amir and then also people connected to her. Using courtship and marriage as a device, Mori-sensei has created a story whose primary aim is ethnographic, and she thus tries to give an objective view of the cultures involved. Even Mr. Smith is a linguist and ethnographer, as well as an excellent method of explaining many aspects of the cultures without forced incursion of a narrator. This is also why she avoids the negative aspects of cultures she's glancing over: sure, she could talk about the negative aspects of the cultures (e.g. polygamy, abuse, and arranged marriages) but, for the purposes of the story, when mentioned, it is in passing. Also disease and illness are addressed to a minor extent, as it is, yet again, not primary (oh, just a point, people do die, not just villains). I should also mention that the complexity of Amir's story and the second bride's tale (Talas) definitely reveal issues found in that region, and that in the fourth brides' (Anis and Shirin) the saccharine feeling is commented on in universe by the nurse as fairytale-like and improbable. Furthermore, daily life is not dramatic, by definition. A story cannot address every single thing imaginable: a story has composition just as much as a picture (i.e. there's a need to pick and choose). Inclusion of rape, bride kidnapping, slavery (not a big issue in that region), and the like is emotionally grabbing and dramatic, which would leave the reader too emotionally involved for Mori-sensei's aims, seeing as it would overshadow the ethnographic details.

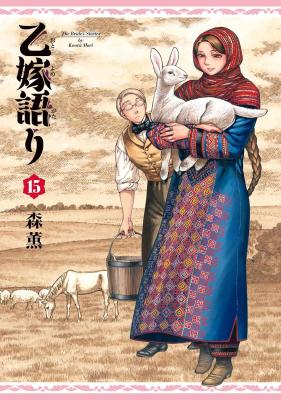

As ever, Mori-sensei's artwork is extraordinary and her storytelling masterful. The extended use of visuals works perfectly. The characters are enjoyable, and their emotions and expressions are complex when the situation asks for it. The pace is enjoyable, and the dashes of humour and periodic dark streaks are lovely and make Otoyomegatari all the more worth while.

If you want a harder or more historical view, rather than an ethnographic one, I would look at Wolfsmund, Shut Hell, or Chang Ge Xing. However, for the aims and scope of the story, Mori-sensei is leaving very few gaps. The detail of her research is also fabulous: down to tiny particulars. Although I really would appreciate translations of blurbs of her research for this story, those are in a separate volume.